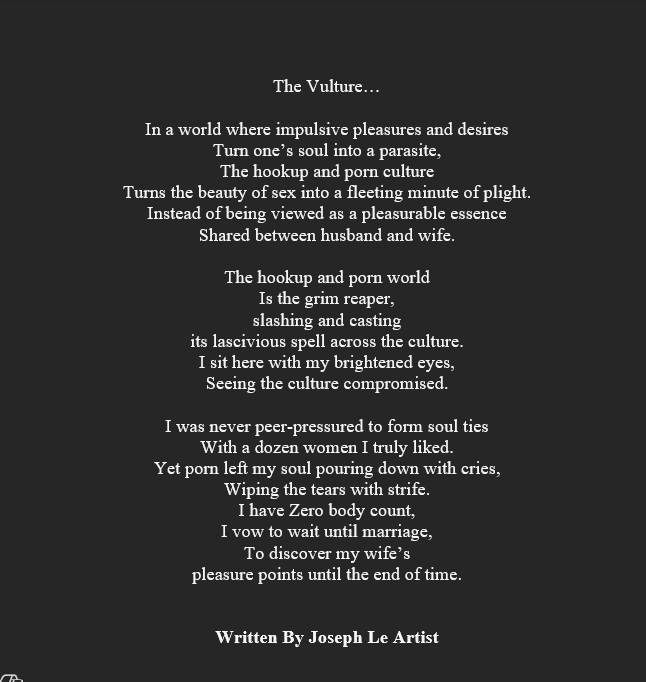

The poem Vultures depict the hook-up and porn culture as reducing sex to a “fleeting minute of plight” resonates deeply with both philosophical and biblical critiques of objectification and alienation. Philosophically, this aligns with existentialist perspectives, such as those of Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Buber, who argue that objectification—treating others as mere objects for gratification—alienates individuals from their authentic selves and undermines genuine human connection. In this view, hook-up and porn culture commodifies intimacy, turning relational beings into tools for fleeting pleasure, thus eroding the possibility of an authentic “I-Thou” relationship, as Buber would describe, where individuals meet in mutual respect and presence.

From a biblical perspective, this critique is enriched by the understanding of sex as a sacred act designed by God to reflect profound spiritual and relational truths. In Genesis 2:24, the Bible states, “Therefore a man shall leave his father and mother and hold fast to his wife, and they shall become one flesh.” This verse underscores the divine intention for sex to be a unifying, covenantal act between husband and wife, fostering intimacy, mutual commitment, and spiritual oneness. Hookup culture, by contrast, fragments this unity, treating sex as a transactional exchange devoid of covenantal love, which the Bible equates with the selfless, sacrificial love of Christ for the Church (Ephesians 5:25).

Pornography further exacerbates this alienation by reducing individuals to mere images for consumption, violating the biblical command to honor the dignity of others as beings created in God’s image (Genesis 1:27). Jesus’ teaching in Matthew 5:28—”But I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lustful intent has already committed adultery with her in his heart”—directly confronts the pornographic mindset, highlighting how lustful objectification dehumanizes both the viewer and the viewed, severing the spiritual connection God intended for human relationships.

Moreover, the poem’s reference to the soul becoming a “parasite” through impulsive desires echoes biblical warnings about the destructive power of sin. Romans 6:12-13 urges believers not to let “sin reign in your mortal body, to make you obey its passions,” but to present themselves to God as instruments of righteousness. Hookup and porn culture, by prioritizing fleeting pleasure over divine purpose, enslaves individuals to their base desires, alienating them from God’s design for holiness and relational flourishing.

The poem’s speaker, by vowing to wait until marriage, embodies a biblical counter-narrative rooted in purity and faithfulness. This aligns with Hebrews 13:4, which declares, “Let marriage be held in honor among all, and let the marriage bed be undefiled, for God will judge the sexually immoral and adulterous.” This commitment reflects a rejection of cultural alienation in favor of a restored relationship with God’s vision for sex as a “pleasurable essence” shared in the sacred context of marriage.

In summary, the poem’s critique of hook-up and porn culture as objectifying and alienating finds a robust parallel in biblical teachings that elevate sex as a sacred, covenantal act. While existentialist philosophy highlights the loss of authentic human connection, Scripture grounds this critique in the divine purpose of human relationships, calling individuals to resist cultural decay through purity, fidelity, and reverence for God’s design. This dual lens reveals the profound spiritual and relational cost of commodifying intimacy, urging a return to a holistic view of love that honours both God and neighbour.