Dissected Threads

Tread One :

Inspired By :

The Quiet Triumph of the authentic youth In certain corners of the world, virtue is punished before it is ever rewarded. To be young, sharp-minded, and clean-handed is to invite contempt. The clever boy who reads instead of robbing, the girl who dreams in metaphors instead of carrying a blade—these are branded as inauthentic, as

Details : Explore the powerful parallels between Jay-Z’s “I Know” and Tragic Hero’s “Mercy,” two hip-hop tracks that personify addiction as a seductive woman. Through vivid metaphors of lust, materialism, and dependency, both songs delve into the emotional and physical toll of temptation, with Jay-Z’s confident swagger contrasting Tragic Hero’s introspective struggle. Poem Treads :

The Quiet Triumph of the authentic youth In certain corners of the world, virtue is punished before it is ever rewarded. To be young, sharp-minded, and clean-handed is to invite contempt. The clever boy who reads instead of robbing, the girl who dreams in metaphors instead of carrying a blade—these are branded as inauthentic, as

Details : Explore the powerful parallels between Jay-Z’s “I Know” and Tragic Hero’s “Mercy,” two hip-hop tracks that personify addiction as a seductive woman. Through vivid metaphors of lust, materialism, and dependency, both songs delve into the emotional and physical toll of temptation, with Jay-Z’s confident swagger contrasting Tragic Hero’s introspective struggle. Poem Treads :

Introduction: A Love Beyond the Veil of Time

In a world captivated by fleeting appearances and societal norms, the poem Her Mature and Seasoned Soul unveils a love that transcends age, judgment, and time itself. With vivid imagery of a woman’s radiant soul and a youthful speaker’s boundless spirit, the poem captures a connection that resonates with the eternal. This soulful bond, where hearts meet beyond the constraints of years, invites us to explore love through biblical wisdom and philosophical depth. As the speaker’s words touch her “mind, body, and soul,” we are drawn into a timeless dance that echoes divine truths and human longing, urging us to see others not by their years but by the weight of their soul’s substance.

The Radiant Soul: A Divine Creation

The poem opens with admiration for her “mature and seasoned soul” and “feminine glow,” a light that captivates the speaker’s heart. Her “youthful caramel skin,” naturally radiant, glistens as a testament to God’s artistry. Psalm 139:14 declares, “I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made; your works are wonderful, I know that full well.” Her beauty is not merely physical but a reflection of the divine imprint within, a soul crafted to shine with purpose and grace.

Biblically, the soul is the eternal essence that connects humanity to God. Genesis 2:7 describes God breathing life into man, making him a “living soul.” Her independence, with her “own cash flow and dividends,” and her yearning to escape the daily grind mirror the biblical call to seek rest in God. Matthew 11:28 offers solace: “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.” Her quest for peace is a spiritual pilgrimage, a longing for the tranquillity found in God’s presence (Philippians 4:7).

The Misjudged Youth: Seeing the Heart

The speaker, perceived as an “immature youth” roaming “like a brute,” faces judgment based on his age and outward demeanor. This superficial view echoes 1 Samuel 16:7: “The Lord does not look at the things people look at. People look at the outward appearance, but the Lord looks at the heart.” His soul, described as “infinite beyond her natural view,” challenges her to see beyond the surface, revealing a depth that defies his years.

Philosophically, this resonates with Plato’s theory of the soul as eternal, existing beyond the physical realm. In Phaedo, Plato suggests that true connection arises when souls recognize eternal truths in one another. The speaker’s ability to touch her with words no man her age has expressed suggests a Platonic ideal of love—one that elevates both toward the divine. His soulful expression disrupts her assumptions, inviting her into a deeper communion of spirits.

The Age Gap: A Bridge of Souls

The poem’s heart lies in the ten-year age gap, prompting her to question, “How is your soul more mature than mine?” This question unveils a universal truth: maturity is not bound by chronology but by the soul’s depth. Proverbs 20:29 celebrates both youth and age: “The glory of young men is their strength, gray hair the splendor of the old.” The speaker’s “old soul” bridges the divide, embodying wisdom that transcends time.

Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia—flourishing through a life of virtue—offers a philosophical lens. The speaker’s expressive depth demonstrates a soul oriented toward meaning, captivating her through authenticity. Their connection illustrates that love, when rooted in the soul, defies temporal constraints. As Soren Kierkegaard might argue, true love requires an authentic leap of faith, a willingness to see the eternal in another. The speaker’s words, flowing from a soul “overflowing through [his] flesh,” embody this leap, forging a bond that surprises and transforms.

The Power of Words: A Soulful Awakening

The poem emphasizes the speaker’s ability to catch her off guard with words that touch her “mind, body, and soul.” This transformative power of language reflects the biblical truth of words as life-giving. Proverbs 18:21 states, “The tongue has the power of life and death.” His expressions, unique and profound, awaken her to a love she hadn’t anticipated, challenging her to reconsider her judgments.

Philosophically, this aligns with Martin Buber’s I-Thou relationship, where authentic encounters between souls foster mutual transformation. The speaker’s words create an I-Thou moment, where both are fully present, their souls laid bare. Her hypnosis and awe at his soulful substance suggest a love that is not merely romantic but existential, a meeting of essences that elevates both toward the divine.

Never Judge by Age: A Call to Discernment

The poem’s exhortation to “never judge a man by his age, but by the weight of his soul’s substance” is a biblical and philosophical mandate. Jesus warns in John 7:24, “Stop judging by mere appearances, but instead judge correctly.” The speaker’s authenticity, as his soul overflows, mirrors Christ’s call to align actions with inner truth. His ability to captivate her reflects a love that sees beyond societal metrics, rooted in the eternal.

Existentially, this aligns with Kierkegaard’s emphasis on individual authenticity. True existence requires living in alignment with one’s innermost self, a principle the speaker embodies. His soulful overflow challenges us to measure others by their essence, not their years, fostering connections that honor the divine spark within.

Conclusion: The Eternal Dance of Souls

In the tender verses of Her Mature and Seasoned Soul, we glimpse a love that transcends the fleeting markers of time, reaching into the infinite depths of the human spirit. The speaker’s words, flowing from an “old soul,” remind us that true connection arises when hearts meet in authenticity, in a sacred space beyond judgment or constraint. As Rumi wrote, “Beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.” In this field, their souls dance, unveiled and eternal, bound by a love that defies age.

Philosophically, this love reflects Heidegger’s Being-toward, where existence is most fully realized in profound connection with another. The speaker’s ability to touch her “mind, body, and soul” is an existential unveiling, a moment where both glimpse the eternal. Her surprise at his maturity challenges us to discern the soul’s weight, to see others as they truly are.

This connection is a reflection of divine love. In 1 John 4:16, we read, “God is love, and whoever abides in love abides in God, and God in him.” Their bond, where words steal hearts and souls overflow, mirrors God’s eternal gaze, which sees the heart’s true substance. Song of Solomon 4:9 captures this divine romance: “You have stolen my heart, my sister, my bride; you have stolen my heart with one glance of your eyes.” Their love is a testament to God’s presence, uniting souls across time and eternity. May we seek such love, sanctified by the soul’s communion with the Divine, where the heart’s weight is the only measure that matters.

Poem Tread :

Inspired By :

The Quiet Triumph of the authentic youth In certain corners of the world, virtue is punished before it is ever rewarded. To be young, sharp-minded, and clean-handed is to invite contempt. The clever boy who reads instead of robbing, the girl who dreams in metaphors instead of carrying a blade—these are branded as inauthentic, as

Details : Explore the powerful parallels between Jay-Z’s “I Know” and Tragic Hero’s “Mercy,” two hip-hop tracks that personify addiction as a seductive woman. Through vivid metaphors of lust, materialism, and dependency, both songs delve into the emotional and physical toll of temptation, with Jay-Z’s confident swagger contrasting Tragic Hero’s introspective struggle. Poem Treads :

The Quiet Triumph of the authentic youth In certain corners of the world, virtue is punished before it is ever rewarded. To be young, sharp-minded, and clean-handed is to invite contempt. The clever boy who reads instead of robbing, the girl who dreams in metaphors instead of carrying a blade—these are branded as inauthentic, as

Details : Explore the powerful parallels between Jay-Z’s “I Know” and Tragic Hero’s “Mercy,” two hip-hop tracks that personify addiction as a seductive woman. Through vivid metaphors of lust, materialism, and dependency, both songs delve into the emotional and physical toll of temptation, with Jay-Z’s confident swagger contrasting Tragic Hero’s introspective struggle. Poem Treads :

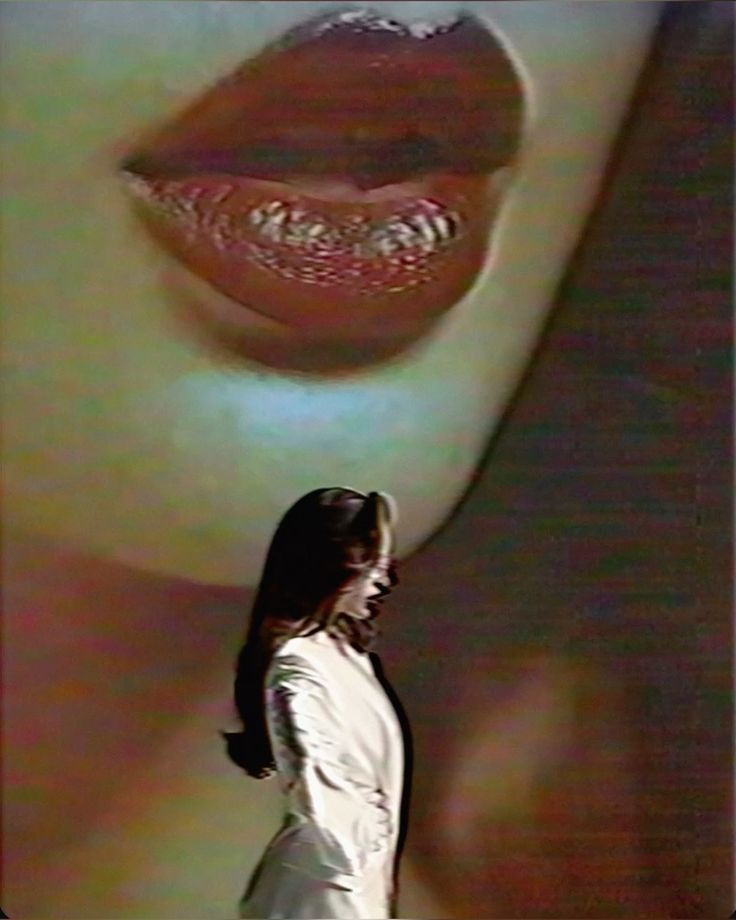

The poem “A Tool of Lucy” presents a chilling narrative of a soul ensnared by sin, embodying the archetype of a cold-hearted predator who spiritually and emotionally devastates others. Through its vivid imagery and raw confession, the poem invites exploration of profound philosophical and biblical themes: the nature of evil, the consequences of free will, and the possibility of redemption. This article examines these themes, drawing on philosophical perspectives and biblical teachings to illuminate the poem’s portrayal of a life consumed by lasciviousness and spiritual destruction.

The Philosophical Lens: Free Will and the Descent into Evil

Philosophically, the poem grapples with the concept of free will and its role in moral corruption. The speaker acknowledges becoming a “tool of Lucy” (likely a reference to Lucifer, the embodiment of evil) “without fighting back,” suggesting a voluntary surrender to destructive impulses. This aligns with existentialist thought, particularly Jean-Paul Sartre’s notion that humans are condemned to be free, bearing full responsibility for their choices. The speaker’s choice of the “Michael Myers archetype”—a symbol of relentless, emotionless violence—reflects a deliberate embrace of a persona devoid of empathy, highlighting the existential weight of choosing one’s path.

From a Nietzschean perspective, the speaker’s “magnificent brute” persona could be seen as an extreme expression of the will to power, where dominance over others (here, through spiritual and emotional manipulation) becomes a perverse assertion of self. Yet, Nietzsche also warns of the nihilistic void that follows such unchecked power, mirrored in the poem’s imagery of a “graveyard” of souls, where the speaker’s actions leave only destruction and emptiness. The philosophical question arises: does the speaker’s surrender to “Lucy” reflect a failure of will to resist, or is it an active choice to revel in chaos?

The Biblical Lens: Sin, Temptation, and Spiritual Death

Biblically, the poem resonates with the narrative of humanity’s susceptibility to sin, rooted in the Fall (Genesis 3). The “seed of lasciviousness” that “bloomed in my youth” evokes the biblical concept of original sin, where the propensity for evil is inherent but activated through choice. The speaker’s predatory behavior—using women’s bodies for pleasure and discarding their “scarred hearts”—parallels the biblical warning against lust as a destructive force. In Matthew 5:28, Jesus teaches that “anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart,” underscoring the spiritual harm of objectifying others.

The reference to “Lucy” taking the wheel suggests a surrender to Satan’s influence, echoing Ephesians 6:12, which speaks of spiritual warfare against “the powers of this dark world.” The speaker’s actions—dismantling souls “for pleasure and ridicule”—reflect the biblical portrayal of Satan as one who seeks to “steal and kill and destroy” (John 10:10). Yet, the poem’s tragic tone, with its admission of being a “fool,” hints at self-awareness, a crack through which biblical hope might enter. Romans 7:24–25 captures this tension: “What a wretched man I am! Who will rescue me from this body that is subject to death? Thanks be to God, who delivers me through Jesus Christ our Lord!”

The Intersection: Redemption or Damnation?

The poem’s philosophical and biblical threads converge in the question of redemption. Philosophically, the speaker’s paralysis and cold-heartedness suggest a life trapped in what Søren Kierkegaard calls “despair,” a state of alienation from one’s true self and God. Kierkegaard argues that despair can only be overcome by embracing faith, a leap that the speaker has not yet taken. Biblically, the possibility of redemption remains, even for the gravest sinners. 1 John 1:9 promises, “If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness.” The poem, however, leaves the speaker in a state of spiritual desolation, with no explicit turn toward repentance, suggesting a cautionary tale about the consequences of unaddressed sin.

Conclusion

“A Tool of Lucy” is a haunting exploration of a soul consumed by lasciviousness and evil, offering a lens through which to examine philosophical questions of free will and moral responsibility alongside biblical truths about sin and redemption. The speaker’s descent into a “magnificent brute” reflects the philosophical peril of unchecked freedom and the biblical reality of spiritual warfare. Yet, both perspectives hold out hope—philosophically, through the possibility of reclaiming authentic selfhood, and biblically, through the promise of divine forgiveness. The poem challenges readers to confront their own choices and the seeds, whether of light or darkness, they allow to bloom within.

Dissected Threads

Tread One :

Inspired By :

The Quiet Triumph of the authentic youth In certain corners of the world, virtue is punished before it is ever rewarded. To be young, sharp-minded, and clean-handed is to invite contempt. The clever boy who reads instead of robbing, the girl who dreams in metaphors instead of carrying a blade—these are branded as inauthentic, as

Details : Explore the powerful parallels between Jay-Z’s “I Know” and Tragic Hero’s “Mercy,” two hip-hop tracks that personify addiction as a seductive woman. Through vivid metaphors of lust, materialism, and dependency, both songs delve into the emotional and physical toll of temptation, with Jay-Z’s confident swagger contrasting Tragic Hero’s introspective struggle. Poem Treads :