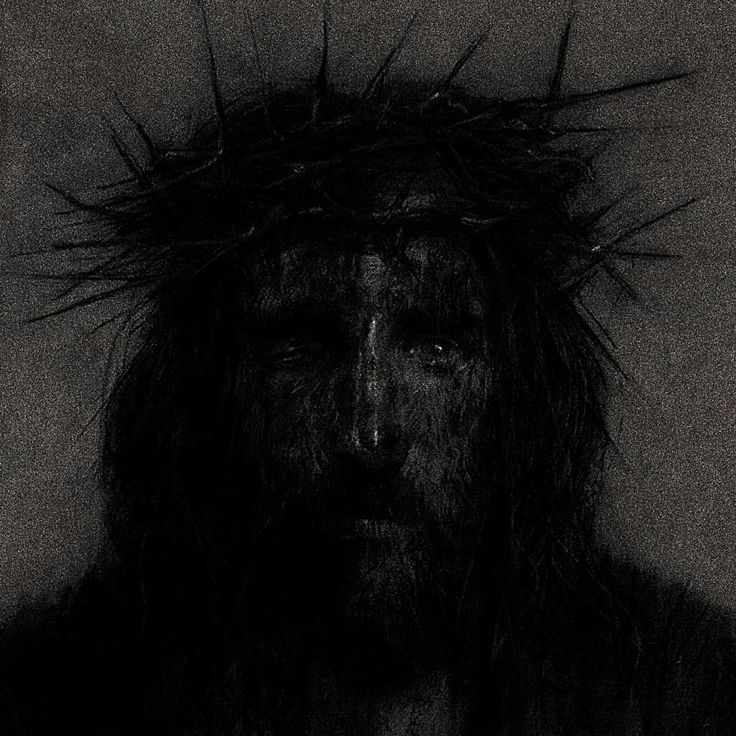

Even though the image of Jesus commonly portrayed in the Western world is historically inaccurate, mockery only carries power when it is directed at the true God—the One who holds authority over the world and the universe. Wearing that specific figure around the neck is not random; it targets the real authority behind the symbol, not merely the image itself.

The core idea here is that symbols transcend their physical or visual form. In semiotics (the study of signs and symbols), a symbol like the cross or an image of Jesus isn’t just an object—it’s a signifier pointing to a deeper signified reality. For Christians, the “true God” referenced is the triune God of the Bible: Father, Son (Jesus as the incarnate Word), and Holy Spirit, who is omnipotent and sovereign over creation (as described in passages like Psalm 115:3 or Colossians 1:16-17).

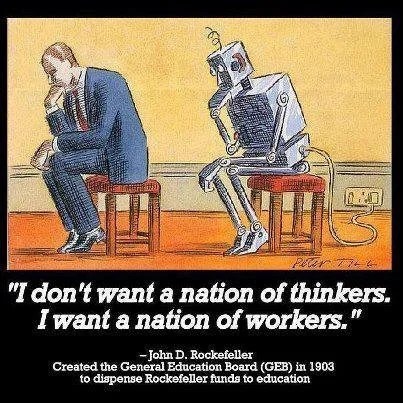

This hinges on a theological assertion: mockery has no inherent power unless it confronts something real and authoritative. In Christian thought, false gods or idols are powerless (e.g., Isaiah 44:9-20 mocks wooden idols as lifeless), so ridiculing them is futile—like punching a shadow. But targeting the “true God” (Yahweh, as revealed in Jesus) invites real consequences because He is the ultimate reality, not a human invention.

Poem Fragment