The poet’s words—“The weight of God’s glory / leaves me hunchbacked, like Notre-Dame. / Still, I am capable of withstanding / and bearing the glorious pain / from the colossal weight in my mind”—strike at the heart of a profound philosophical tension: the encounter between the finite human self and the infinite divine. This brief yet evocative verse serves as a lens through which to explore the existential and metaphysical implications of divine presence, the nature of human suffering, and the paradoxical strength found in submission to a transcendent burden.

The Weight of Transcendence

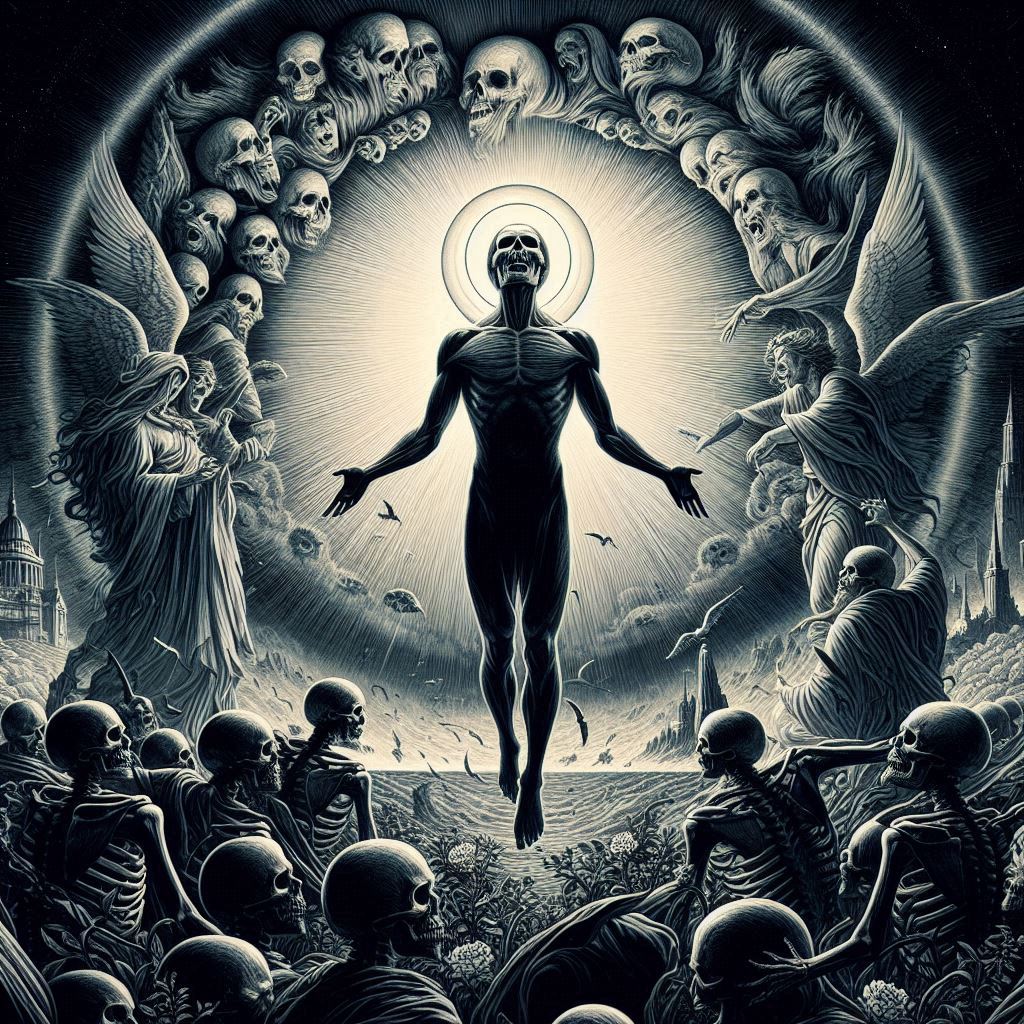

To speak of “God’s glory” is to invoke the sublime—a concept that philosophers like Immanuel Kant and Edmund Burke have described as an experience of awe mingled with terror, where the infinite overwhelms the finite. The poet’s imagery of being “hunchbacked, like Notre-Dame” captures this encounter vividly. Notre-Dame, whether understood as the cathedral or Victor Hugo’s Quasimodo, symbolizes endurance under immense pressure. The cathedral, a monument to divine aspiration, bears the scars of time—its gargoyles and spires weathered yet resolute. Quasimodo, deformed by his physical burden, embodies a soul capable of profound love and sacrifice. The poet’s “hunchbacked” posture is not merely physical but existential: the self, bent under the weight of divine encounter, is reshaped by the recognition of its own finitude against the infinite.

This weight is not merely oppressive but transformative. In the philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard, the encounter with the divine is a moment of “fear and trembling,” where the individual confronts the absurdity of faith—the paradox of embracing a truth that transcends reason. The “weight of God’s glory” can be seen as this Kierkegaardian leap, where the self is both shattered and reconstituted by its confrontation with the Absolute. To be hunchbacked is to bear the mark of this encounter, a visible sign of having wrestled with the divine, much like Jacob’s limp after his struggle with the angel.

The Glorious Pain

The poet’s assertion—“Still, I am capable of withstanding / and bearing the glorious pain”—introduces a dialectic of endurance and suffering. The phrase “glorious pain” is a profound oxymoron, echoing the Christian mystical tradition of figures like St. John of the Cross, who spoke of the “dark night of the soul” as a painful yet purifying path to divine union. Philosophically, this pain aligns with Martin Heidegger’s notion of Geworfenheit (thrownness), the human condition of being cast into existence without choice, burdened by the weight of Being itself. Yet, the poet’s claim of capability suggests an active response to this thrownness—a refusal to be crushed by the burden.

This resilience resonates with Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of amor fati—the love of one’s fate. To bear the “glorious pain” is to embrace the suffering inherent in divine encounter, not as a passive victim but as a participant in a greater meaning. The glory lies not in the absence of pain but in its transformative potential, where suffering becomes a crucible for the self’s becoming. The poet’s endurance is not stoic detachment but a dynamic engagement with the divine, a willingness to carry the weight even as it bends the soul.

The Colossal Weight in the Mind

The final line—“from the colossal weight in my mind”—shifts the locus of this burden to the interiority of the self, inviting a phenomenological reflection on consciousness and its limits. The mind, as the seat of perception and understanding, becomes the arena where the divine is both apprehended and contested. This “colossal weight” evokes the overwhelming nature of divine truth, which resists containment within human categories. In the philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas, the encounter with the Other—whether human or divine—disrupts the self’s autonomy, imposing an ethical and existential weight that demands response. The “colossal weight in my mind” is thus the trace of the infinite within the finite, a presence that unsettles yet enriches the self’s understanding of itself and its place in the cosmos.

This interior burden also recalls Plato’s allegory of the cave, where the philosopher, having glimpsed the light of truth, returns to the cave burdened by knowledge that isolates and transforms. The “colossal weight” is the price of this vision—a cognitive and spiritual load that reshapes the self’s orientation toward reality. Yet, the poet’s declaration of capability suggests that this weight, though immense, is not paralyzing. It is a burden that the self can bear, not through its own strength alone but through a paradoxical participation in the divine glory that both wounds and sustains.

The Human Condition and Divine Encounter

The poem, in its brevity, encapsulates a universal human experience: the tension between finitude and infinity, suffering and transcendence. It challenges the modern inclination to seek comfort and certainty, proposing instead that true meaning lies in embracing the glorious pain of divine encounter. This is not a masochistic celebration of suffering but a recognition that the divine—whether understood as God, truth, or Being—demands a response that transforms the self. To be hunchbacked is to bear the mark of this transformation, a visible sign of having stood in the presence of the infinite.

In the end, the poet’s words invite us to reconsider our own burdens—spiritual, existential, or otherwise. What does it mean to carry the weight of glory? It is to live in the tension between awe and agony, to endure the bending of the self without breaking, to find strength in the very weight that humbles us. Like Notre-Dame, we may be weathered; like Quasimodo, we may be bent. But in bearing the colossal weight, we discover our capacity to withstand, to hold fast to the glorious pain, and to emerge not diminished but deepened by the encounter with the divine.